What is Lyophilization?

Lyophilization vs. Freeze Drying

What is lyophilization? How does it work?

Lyophilization and freeze drying are synonymous. Lyophilization is a water removal process typically used to preserve perishable materials, to extend shelf life or make the material more convenient for transport. Lyophilization works by freezing the material, then reducing the pressure and adding heat to allow the frozen water in the material to sublimate.

Lyophilization’s 3 Primary Stages

Lyophilization occurs in three phases, with the first and most critical being the freezing phase. Proper lyophilization can reduce drying times by 30%.

Freezing Phase

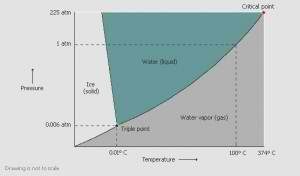

There are various methods to freezing the product. Freezing can be done in a freezer, a chilled bath (shell freezer) or on a shelf in the freeze dryer. Cooling the material below its triple point ensures that sublimation, rather than melting, will occur. This preserves its physical form.

There are various methods to freezing the product. Freezing can be done in a freezer, a chilled bath (shell freezer) or on a shelf in the freeze dryer. Cooling the material below its triple point ensures that sublimation, rather than melting, will occur. This preserves its physical form.

Lyophilization is easiest to accomplish using large ice crystals, which can be produced by slow freezing or annealing. However, with biological materials, when crystals are too large they may break the cell walls, and that leads to less-than-ideal freeze drying results. To prevent this, the freezing is done rapidly. For materials that tend to precipitate, annealing can be used. This process involves fast freezing, then raising the product temperature to allow the crystals to grow.

Primary Drying (Sublimation) Phase

Lyophilization’s second phase is primary drying (sublimation), in which the pressure is lowered and heat is added to the material in order for the water to sublimate. The vacuum speeds sublimation. The cold condenser provides a surface for the water vapor to adhere and solidify. The condenser also protects the vacuum pump from the water vapor. About 95% of the water in the material is removed in this phase. Primary drying can be a slow process. Too much heat can alter the structure of the material.

Secondary Drying (Adsorption) Phase

Lyophilization’s final phase is secondary drying (adsorption), during which the ionically-bound water molecules are removed. By raising the temperature higher than in the primary drying phase, the bonds are broken between the material and the water molecules. Freeze dried materials retain a porous structure. After the lyophilization process is complete, the vacuum can be broken with an inert gas before the material is sealed. Most materials can be dried to 1-5% residual moisture.

Problems To Avoid During Lyophilization

- Heating the product too high in temperature can cause melt-back or product collapse

- Condenser overload caused by too much vapor hitting the condenser.

- Too much vapor creation

- Too much surface area

- Too small a condenser area

- Insufficient refrigeration

- Vapor choking – the vapor is produced at a rate faster than it can get through the vapor port, the port between the product chamber and the condenser, creating an increase in chamber pressure.

Important Lyophilizer Terms

Here are a few important lyophilization terms. For a comprehensive list, see our freeze drying terminology page.

Eutectic Point or Eutectic Temperature

Is the point at which the product only exists in the solid phase, representing the minimum melting temperature. Not all products have a eutectic point or there may be multiple eutectic points.

Critical Temperature

During lyophilization, the maximum temperature of the product before its quality degrades by melt-back or collapse.

Crystalline

The material forms crystals when frozen.

- Has a eutectic point or multiple eutectic points

- Fast freezing creates small crystals which are hard to dry

- Annealing can help form bigger crystals

Amorphous

- Does not have a eutectic point

- For amorphous materials, freeze drying needs to be performed below the glass transition temperature

Collapse

The point at which the product softens to the extent that it can no longer support its own structure. This can be a problem for many reasons:

- Loss of physical structure

- Incomplete drying

- Decreased solubility

- Lots of ablation (splat)